🎧 One Simple Metric To Rule Them All

Gross Domestic Product (or GDP) is the value of all finished or final goods and services produced domestically in a year. I pull apart the definition in this post.

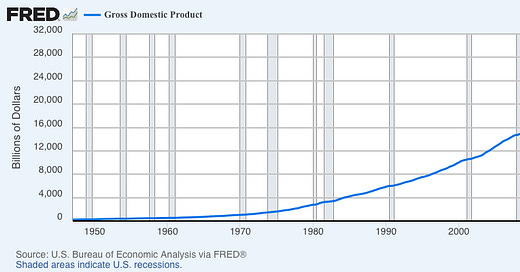

To fully understand the economy, we need to start with its most important concept—GDP.

Gross Domestic Product (or GDP) is the value of all finished or final goods and services produced domestically in a year.

In other words, GDP adds together all goods and services made in one country during a year.

There is also a GDP calculation for the global economy. It’s currently at $105 trillion in US dollars. There are four key words to pull out of the definition: value, final, produced, and domestic.

What economists mean by value

Value in economics means the price.

To add everything together, we need to account for different prices. If you’ve ever heard the phrase, “you can’t add apples and oranges,” then you know what I mean.

Apples and oranges can have different prices. There’s a seasonal difference in prices. Apples are more plentiful, and cheaper in the fall. Oranges have a seasonal window too.

In winter, oranges and other citrus are in season and cheaper. The seasons matter in calculating GDP.

Most of us consume oranges as juice. And we can get them all year long. This is true of most goods. But goods can vary in terms of their value, or the price we’re willing to pay.

An apple is cheaper than a haircut which is cheaper than a plane ticket which is (usually) cheaper than a car.

We can’t just add all of that together to get GDP. We need their prices.

Collecting "their prices also helps us, or rather the Bureau of Labor Statistics, calculate inflation, as we noted in “When Is an Apple not an Apple?”The second word we pulled out was “final or finished.”

What “final goods and services” means

A final good is the one sold to its end user.

For example, a potato I buy to make stew is a final good. But if McDonalds buys a potato to make French fries, then the potato isn’t the final good—the French fries are.

The same is true for a laptop. If you buy a laptop for your personal use, then it’s a final good. However, if a business that makes education software gives a laptop to a salesperson to help them do their jobs, then it isn’t a final good. The software the company sells is.

That laptop used for sales might lead to a sale of the product in a different year. Or even two years later.

What we mean by produced, domestic, and year

We count production of goods and services to help us get to GDP.

We leave out goods that weren’t made that year.

For instance, if Ford makes a truck in 2024, but doesn’t sell it until 2025, it counts in GDP for 2024. It goes into a category called “Changes in Inventory” which is part of a broader component called Investment.

And if the good is made somewhere else, it’s part of imports which get subtracted from GDP.

Let’s put this all together with an example.

An example

Suppose my hairdresser buys new scissors and a new handheld hair dryer in December 2024. She also buys a hair product from an American producer in January 2025 to help her “finish” curly hair.

Let’s suppose the scissors are made in North Carolina and the hair dryer in China. And let’s ignore taxes.

I get my hair cut in February 2025. What goes into GDP and when?

1. The scissors go into Investment, another part of GDP, in 2024.

2. The hair product goes into GDP in 2025 as Consumption. The hairstylist will subtract it from her taxes as cost of goods sold.

3. The hair dryer gets subtracted from GDP in 2024, because it’s part of Imports.

4. The amount I pay for the haircut and tip goes into Consumption, a very important of GDP, in 2025.

Those taxes we ignored? Those aren’t goods or services produced. Look at the definition again!

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the value of all finished or final goods and services produced domestically in a year.

We’ll talk about who spends those tax revenues when we discuss Government Spending and Investment.

Where we’ll go next

You can start to see where these next few posts will go. We’ll dive into the American consumer and the role of households. We’ll look at Investment, which is a different word from investments, a word financial advisors use.

In case you’re interested: putting money into investments, like savings and stocks, doesn’t itself add to GDP. Any sales expenses you pay does count, though.

We’ll continue with a look at Government Spending and Investment and Exports and Imports.

Then we’ll finish with a discussion of some of the problems we have when we measure GDP and growth.

Thank you for reading!

Nikki

Notes:

[1] If you’re not allergic to numbers, check out this Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) breakdown of these “components” for the US, here:

https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/real-gdp-major-demand-category.htm

Even if you are, have a look at the categories and ignore all the data on the right.

[2] Here’s the article I referred to earlier:

A Look at How the Inflation Rate Gets Calculated

I, like most economists, look to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for pricing and employment information.

This was a great explanation! I am impressed with the research and thought that went into this. I’ll never think of gdp the same 😁

Hi Nikki. A few things: a. Congratulations on your book deal! So exciting. b. On GDP, there is always been a nuance that has bothered me, but I haven't resolved it. Specifically, let's say Ford makes an F150 truck and sells it for $80k. Assume the cost of goods sold to make the truck is $50k. Further, assume those numbers (sales and COGS) are identical two years in a row. In year X - all of the $50k was purchased from domestic companies. and year X+1: none of the $50k was purchased from domestic companies (all international purchases). How would this change manifest itself in our GDP?