Magic: The Gathering Cards and Government Bonds

What do they have in common? They both have prices.

In the post, In Balance: How Banks Create Money, we learned about banks. [1] Here’s what we know:

· Banks take in deposits from customers.

· Banks keep some of that available as required reserves.

· A bank must meet its minimum required reserves every day.

· Banks have to make sure that they have enough in cash and on reserve.

If they don’t have enough funds, they have to borrow what they need. If they have extra funds, they can loan those to other banks. This creates a market for excess reserves.

We also learned from the earlier post that banks also hold assets in the form of government bonds.

Profits motivates banks, as it does for all businesses. The higher their profits, the happier their investors will be. Banks maximize profits by making loans with excess reserves. Some banks choose less risky loan strategies. This can result in some extra funds that are not in use to make profits.

Some choose more risky loan strategies. Or a bank may have had unusual activity. They could wind up falling short of the federally mandated requirement. The overnight market exists to help banks ensure that they’re in balance and meet their requirements. [2]

The federal funds rate

The rate that banks charge each other in the overnight market is called the federal funds rate.

That rate can change if the Federal Reserve (the Fed) releases more money into or withdraws money from the market. The Fed does this by getting banks to change their excess reserves. In the specific case of rising inflation, the Fed wants to get banks to give up their excess reserves and loan out less.

Government bonds are like Magic the Gathering cards and other collectibles because they have prices. An asset only has a price if it can be traded in a market.

What can I do to get you to give an asset up? I have to offer you a price that is higher than what you currently value it at. With Magic cards, buyers have to offer enough convince the seller to give up the card.

For government bonds, the same is true. The Fed has to offer banks a higher price than the bonds’ current value.

How bonds (and other assets) work

That value of a government bond is its coupon value. At the end of a specified number of months or years, government bonds pay a certain amount. [3] That amount will depend on the interest rate attached to the bond. To keep the computation simple, let’s look at a certificate of deposit (CD).

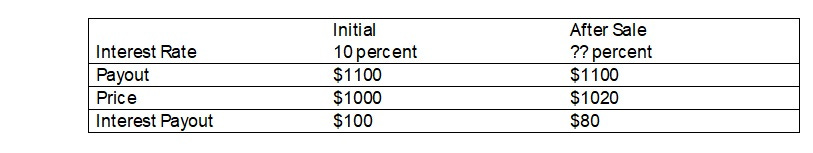

Suppose you bought a CD for $1000 with a 10 percent simple annual interest rate that will pay you in one year. If you had a $1000 and could afford to let it go for a year, you would snap it up right? You would get, at the end of the year, your $1000 plus 10 percent for giving up your money for a year. That would amount to $1100.

Most CDs are not transferable, that is you can’t give them to someone else or sell them. But suppose you could sell yours? How much would it take for you to give it up tomorrow?

Economists would tell you any number over $1000. Let’s keep it simple. Suppose your friend Linda offered you $1020 for the bond tomorrow. Would you sell it then? Consider the cost of holding on to the bond for 364 more days versus getting your money back plus $20 for you trouble? Is it worth the $80 you would give up? Suppose it was. What changes?

Notice the difference. The price has changed, but the payout hasn’t. This caused the interest rate to change. A little easy division and the new interest rate for Linda is about 7.8 percent. [4]

By changing the price, the interest rate changes. Here we raised the price on the CD, causing the interest rate to fall. The price and interest rate move in opposite directions.

The same is true for government bonds. If we raise the price, the interest rates falls. And vice versa. Lowering the price on bonds causes the interest rate to rise, because the total payout doesn’t change.

We have discovered that to lower the money supply, the Fed needs to reduce excess reserves banks hold. To do that they increase the interest rate to get banks to hold bonds. The Fed does this by raising the prices of bonds. And they do all that to reduce inflation.

Which was the goal!

In the last piece of our Crash Course on Inflation, we’ll wrap all this up.

Thanks for taking the time to read. I do appreciate it.

Nikki

PS: I’m in Nashville for Bouchercon. I hope all of you in the US and Canada enjoy your Labo(u)r Day weekend!

[1] https://nikkifinlay.substack.com/p/in-balance

[2] What happens if they’re not? If you’ve ever watched the beginning of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” you know the answer. We’ve also seen a run on the bank in March 2024 with Silicon Valley Bank. Customers got upset. Investors lost money. And the government wanted to know what happened.

[3] We have to ignore certain government bonds, like Series EE bonds, which work differently.

[4] The new interest rate is 80 (the interest payout) divided by 1020 (the price).