During our discussion of inflation, we learned that inflationary pressures happen when there was an inward shift in supply.

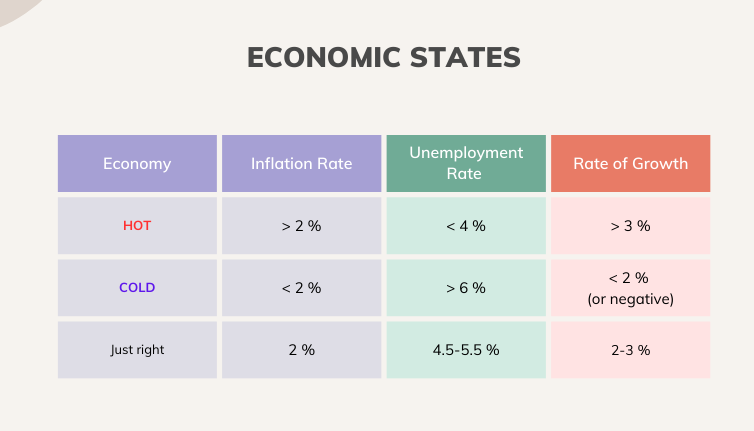

Last week we studied the indicators of a hot economy: high inflation and low unemployment. This week we’ll look at an economy that is too cold, focusing on the recession of 2007-2009, aka the Great Recession.

This Economy is too cold!

Poor borrowing and lending practices led to the Great Recession. [1][2]

In 1999 the subprime market for mortgages emerged. Lower income households and those with lower credit scores could buy a home with a variable interest rate and less documentation.

When the Federal Reserve increased interest rates to 4.5 percent in 2007, rates on these mortgages rose. [3] By 2007, almost a quarter (25 percent) of borrowers had mortgage payments they couldn’t afford. Mortgage debt increased to 97 percent of GDP.

In 2008 the housing and stock markets crashed.

Almost four million people lost their homes.

My husband and I watched our retirement get slashed in half. We were also upside down on our mortgage. Most Americans create wealth by buying homes and stocks. Median wealth fell from $106,000 to $62,200 during the recession.

The US lost production and income. Real GDP fell by 4.3 percent.

Approximately 1.8 million businesses closed, and 7.8 million employees lost their jobs. We were lucky. We kept working, although I had to take six furlough days in 2009. Households who still had their jobs weren’t sure they were going to keep them.

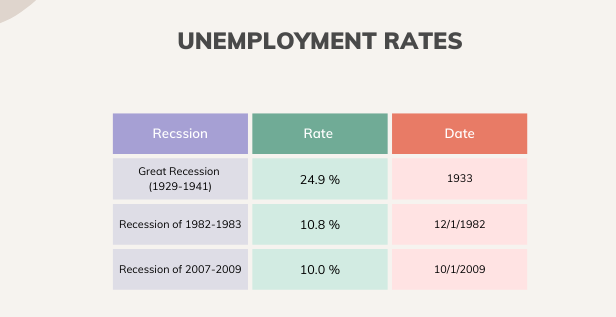

They reduced spending. Less spending decreased the need for output and for employees to produce that output. The unemployment rate soared to 10.0 percent by October 2009. [4]

When is the unemployment rate too high?

The unemployment rate is too high when it is over 5.5 percent. There are fewer job openings than there are job seekers, and it takes them longer to find work. The highest rates happen during recessions.

(The BLS didn’t publish monthly data until 1948.)

During recessions, frictionally unemployed workers take longer to find jobs and structurally unemployed job seekers can’t find work. [5]

Who is what?

To better understand what happened, let’s take another look at the types of unemployment. Last time we learned that there are three types: frictional, structural, and cyclical. Why is it important to use these categories? When we know the different types of unemployment, we can design better policies to help.

Frictional unemployment occurs when someone is moving from one job to another or entering the labor market. The job exists, the job seeker just has to find it.

Structural unemployment is involuntary. The job has gone away and is not coming back. The economy needs different kinds of workers due to changes in technology, skills shifts, or offshoring.

Cyclical unemployment happens when the rate deviates from the natural rate, which is the frictional rate plus the structural rate.

Let’s identify who falls into our categories, using some of the people we introduced in It All Started with an Argument.

Marcus, who has a college degree, looks for a job each week, even though his unemployment benefits have run out. He’s young and geographically mobile.

Jamie keeps looking for work, taking any job he can get, for as many hours as he can. He never completed high school and is currently working about 10 hours a week as a janitor for a small shop. Jamie keeps looking for a better job with more hours.

Leanna collects her unemployment benefits, but instead of going back to her old job she’s decided to go back to school and get certified for a new career.

Silvie was laid off from her job as an administrative assistant but hasn’t found work in over a year. She has her GED but finds it difficult to learn the skills she needs to find a decent job. Silvie’s stopped looking, but still wants to work.

Marcus is frictionally unemployed because he expects to find work. He may be looking for work in a location he’s not familiar with, so the search will take longer. What about the others?

Leanna doesn’t fit any of our definitions and is not in the labor force. Leanna’s situation shows us why we don’t use the benefits rolls to calculate the unemployment rate.

Jamie isn’t unemployed, but he is underemployed. In his case, a skills shift has interfered with his ability to find a good job. Silvie is structurally unemployed. Like Jamie, her skill set doesn’t meet current workplace needs.

Any of these people could be suffering from cyclical unemployment too.

Downward shifts in demand causes recessions. A change in demand causes changes in how many potential jobs there are or can change the type of work that businesses value.

After the Great Recession high tech jobs, which require a distinct set of skills and knowledge, became more common. The industry enjoyed almost zero percent unemployment until recently.

This Economy is just right!

Just as Goldilocks found that the baby bear’s food, chair, and bed were just right, the US knows when the economy is just right.

The economy was at its peak from 1983-2000.

Households face hardships face when the economy is not just right. For example, during the Great Recession, food insecurity rose by 3.8 percent. In later posts, we’ll look at the problems, causes, and short- and long-term solutions to unemployment.

As always, thank you reading. Comments and suggestions welcome!

Nikki

[1] For a more detailed analysis of the crisis, see John Weinberg, The Great Recession and Its Aftermath, 10/22/2013. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-and-its-aftermath.

[2] Ben Bernanke, one of the 2022 Nobelist in Economic Sciences, was the Chair of the Federal Reserve at the time.

[3] Mortgage rates are tied to the federal funds rate.

[4] On a personal note, we did go on a short cruise in the Caribbean. Once people learned what I did, they kept asking, “what should we do now?” I told people not to panic, and to just go back to work. Of all the economies that slipped into recession in 2008, the American economy was the one to back.

[5] A depression is a deep, long recession.